PART 1

Securing Human Well-Being:

Toward a Conceptual Framework

|

|

|

|

PART 1

Securing Human Well-Being:

Toward a Conceptual Framework

The Canadian social security system is usually thought of as a bundle of rights and programs that collectively constitute a "social safety net." The metaphor "safety net" is instructive. It implies that normally people have what they need, and that the net is a kind of insurance against catastrophe if it should happen that someone "falls" off from the platform of "normal" self-reliance and prosperity. The Canadian social safety net is made up of a blend of income security, health and social insurance programs and a constantly changing array of "social adjustment" services, designed to help those who are having difficulty staying on the platform to "adjust" to mainstream expectations.

The principal mechanisms of the Canadian social security system include social assistance, employment insurance, the Canada Health Plan, the Canada and Quebec Pension Plans, Old Age Security and guaranteed income supplements for seniors, housing programs for low income people, and a somewhat transient array of other programs that come and go depending on political spending priorities and available cash, including education and training subsidies, tax credits, and programs aimed at helping "disadvantaged" groups to find their place within the mainstream of Canadian social and economic life.

A basic assumption of the Canadian social security system is that only ten percent of the population will ever really need the safety net, and that between ninety and ninety-three percent will remain healthy, and secure in their place on the platform of mainstream prosperity. Mac Saulis points out that in many Aboriginal communities over ninety percent of the population would have to be categorized as being out of the mainstream in terms of their current reliance on social assistance, housing subsidies and other aspects of the social safety net.

In the Introduction to this document, we began our discussion with a fundamental assertion that merely tinkering with and adjusting the Canadian social security system for Aboriginal communities has not, and will not, work. We believe that a starting place for Aboriginal social security reform must be to re-conceptualize what social security actually means for Aboriginal people, such that what is "secured" is human well-being and prosperity, or what the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People refers to as "whole health" (RCAP, Vol. 3:34).

The following points summarize the implications of that starting place for this discussion.

When conceived in this way, the delivery of programs to and for communities, (no matter how generously funded or effectively designed) can never bring "social security" to Aboriginal people. Until Aboriginal communities can recover the wealth they once possessed in the form of healthy social relationships, well-being will continue to be an illusive goal. Those culturally generated relationships provided pathways of opportunity for self-development and contributing to the social and economic well-being of the people, as well as a dependable safety net for those who fall upon hard times for whatever reasons.

This safety net was animated by love, sharing and caring, and it was maintained through healthy relationships of respect, trust and mutual responsibility as well as effective leadership.

These community capacities are sometimes referred to as "social capital". What is implied by reconceptualizing social security in the way we have is that in addition to certain financial security and "social adjustment programs, it will be critical to invest in the rebuilding (i.e. healing and development) of the fundamental relationships that generate and protect human well-being. Only then can a sustainable system of "social security" be built for Canadian Aboriginal communities.

2. As we stated in our introduction, a healthy person, family, community or nation are those who are able to successfully address the fundamental determinants of health.

3. Aboriginal communities (both on reserve and in urban settings) are suffering from a complex web of health and social problems that have their roots in generations of systemic oppression, which has included a litany of atrocities and injustices that would now be considered flagrant crimes against humanity according to the Geneva Accords. A practical list of these includes the psychological, physical, spiritual and sexual abuse of Aboriginal children in residential schools: systemmic government and church-based attempts to uproot and destroy Aboriginal spirituality, cultures, language and identity, appropriation of Aboriginal lands and resources and subsequent destruction of local economies followed by enforced and prolonged ghettoization (the reserve system), poverty and dependency on a debilitating welfare system; and grinding racism encountered most noticeably in school, in the justice system, in attempts to secure employment, and in basic human relations with non-Aboriginal communities. Many of these patterns are still happening today.

4. Much of this externally originated oppression has also been internalized. "Internalized oppression" refers to the phenomena of oppressed people turning their hurt and anger on themselves and on each other (Memmi, 1967; Jackins, 1978; Freire, 1970). Examples of internalized oppression in Aboriginal communities include physical and sexual abuse, alcohol and drug addiction, suicide, criminal violence, public corruption and repression, learned economic helplessness and dependency, generational disunity between families, and racial/cultural self-hatred.

5. As we have described in our introduction, healing in Aboriginal communities may be strategically defined as a process of removing barriers and building the capacity of people and communities to address the determinants of health.

6. In order to assist Aboriginal communities to address the full range of determinants of human well-being and prosperity, it is necessary to have a comprehensive understanding of the following.

b. How can communities assess their current realities and conditions in order to determine health states (i.e. where things are now) relative to each determinant?

c. What are the basic status principles and processes of change that are needed in order to bring about improvements in levels of well-being relative to each of the determinants of health?

In their book, Why Some People are Healthy and Others are Not, Evens, Barer and Marmor (1994) draw together a useful synthesis of work that spans at least a dozen disciplines as they compile available evidence on the critical conditions and factors that determine human health. Their work was proceeded by a number of creative leaps in health thinking that gradually encouraged a considerable broadening of perspective from the dominant medical model, "which tends to focus on disease rather than health, and is preoccupied with bio-mechanical problems and solutions". (Evans & Stoddard, 1994: 31)

In Canada, milestones in health thinking can be traced as follows.

b. The way to change behaviour is to give people information, i.e. to educate them about the harmful affects of poor health choices and behaviours.

c. Once people have been properly educated they will make healthy choices and they will change behaviours negatively affecting their health.

2. 1978 - The World Health Organization and UNICEF held a landmark conference in Alma-Ata, Russia from which the now famous "Alma-Ata Declaration" emerged, and from which the World Health Organization later developed a "Health for All" strategy. The Alma-Ata Declaration is significant because it further expanded the definition of "health" to include "complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease." It went on to declare that health is a "fundamental human right," that "gross inequity in health status between the haves and the have nots of the world is politically, socially and economically unacceptable," and that "people have the right to participate individually and collaboratively in building health solutions." The Alma-Ata Declaration focused on primary health care, which brings medical services and community health development into the same sphere of activity.

3. The next major shift could be seen in the "Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion," released at the First International Conference on Health Prevention, hosted by Canada in Ottawa in 1986. The Ottawa Charter specifically listed the following "prerequisites" to determinants of health.

4. It has only been during the past four years that non-medical determinants of health were officially integrated into a national policy framework in Canada. This thinking was synthesized in a document called "Strategies for Population Health: Investing in the Health of Canadians" which was approved by the Federal / Provincial / Territorial Ministers of Health in 1994.

What is significant here is that a framework for rethinking what Canada’s health agenda should be (i.e. how money is spent) was developed and agreed upon. That framework calls for an investment in the work of addressing the determinants of health, and lists those determinants as follows.

b. Social support networks

c. Education

d. Employment and working conditions

e. Physical environment

f. Biology and genetic endowment

g. Personal health practice and coping skills

h. Healthy child development

i. Health services

We share this brief history of health thinking in Canada for the following reasons:

2. A careful examination of the literature on determinants of health, and particularly the actual listed determinants that are identified in the published sources and the integrative models being proposed by groups such as the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research seem to us to be a rediscovery of things Aboriginal elders knew many generations ago, and also things that virtually all of the great spiritual traditions of humanity have taught since time immemorial regarding the maintenance of harmony and balance within ourselves as individuals, in our personal relationships, in our family and community life, in the pursuits and activities of our nations and in our fundamental relationships with the earth and the Creator.

In our professional practice, we have undertaken a simple and extremely revealing exercise in dozens of Canadian and American Indigenous communities, as well as in many non-Aboriginal settings in both rural and urban settings.

A representative cross-section of community members are gathered in a meeting or workshop. There are usually children, youth, men, women, elders, professionals, unemployed people, traditionalists, entrepreneurs -- as wide a diversity of people as we can get.

We then ask variations of the following "simple" question: "What is it that people here need to have in their lives in order to have a good life, to have well-being and prosperity?" The results have been remarkably similar across many communities and cultures and also quite constant with what the "experts" are now saying in the research literature.

What follows is a synthesis of this thinking, drawn from work with First Nations, Inuit, and Metis communities across Canada between 1994 and 1998. This list should not be seen as a model to be copied, but rather a proof that in Aboriginal communities people already know what the determinants of health are and that part of our work in promoting community healing is to mirror back to them what they already know in ways that promote learning and action.

The Determinants of Health to be "Secured" in Social Security Reform

Health status relative to each of the following determinants needs to be defined (in terms of a local community standard of well-being), measured and assessed (in terms of current realities and conditions) and analyzed (in terms of what is needed to transform health conditions.

2. Spirituality and a sense of purpose - connection to the Creator and a clear sense of purpose and direction in individual, family and community life, as well as in

the collective life of the nation.

3. Life-sustaining values, morals and ethics - guiding principles and a code of conduct that informs choices in all aspects of life so that at the level of individuals, families, institutions and whole communities, people know which pathways lead to human well-being, and which to misery, harm and death.

4. Safety and security - freedom from fear, intimidation, threats, violence, criminal victimization, and all forms of abuse both within families and homes and in all other aspects of the collective life of the people.

5. Adequate income and sustainable economics - access to the resources needed to sustain life at a level that permits the continued development of human well-being, as well as processes of economic engagement that are capable of producing sustainable prosperity.

6. Adequate power - a reasonable level of control and voice in shaping one's life and environment through processes of meaningful participation in the political, social and economic life of one’s community and nation.

7. Social justice and equity - a fair and equitable distribution of opportunities for all, as well as sustainable mechanisms and processes for re-balancing inequities, injustices and injuries that have or are occurring.

8. Cultural integrity and identity - pride in heritage and traditions, access to and utilization of the wisdom and knowledge of the past, and a healthy identification with the living processes of one's own culture as a distinct and viable way of life for individuals, families, institutions, communities and nations.

9. Community solidarity and social support - to live within a unified community that has a strong sense of its common oneness and within which each person receives the love, caring and support they need from others.

10. Strong families and healthy child development - families that are spiritually centered, loving, unified, free from addictions and abuse, and which provide a strong focus on supporting the developmental needs of children from the time of conception through the early years and all the way through the time of childhood and youth.

11. Healthy eco-system and a sustainable relationship between human beings and the natural world - the natural world is held precious and honoured as sacred by the people. It is understood that human beings live within nature as fish live within water. The air we breath, the water we drink, the earth that grows our food and the creatures we dwell among and depend on for our very lives are all kept free from poisons, disease and other dangers. Economic prosperity is never sought after at the expense of environmental destruction. Rather, human beings work hand-in-hand with nature to protect, preserve and nurture the gifts the Creator has given.

12. Critical learning opportunities - consistent and systematic opportunities for continuous learning and improvement in all aspects of life, especially those connected to key personal, social and economic challenges communities are facing, and those which will enhance participation in civil society.

13. Adequate human services and social safety net - programs and processes to promote, support and enhance human healing and social development, as well as to protect and enable the most vulnerable to lead lives of dignity and to achieve adequate levels of well-being.

14. Meaningful work and service to others - Opportunities for all to contribute meaningfully to the well-being and progress of their families, communities, nations, as well as to the global human family.

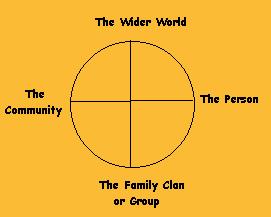

We often ask people to display their

thinking about determinants in labeled circles or balloons on a large sheet

of paper (see diagram at the top of the next page). We then ask participants

to select one determinant (for example, strong families) and to draw connecting

lines to the other determinants that must also be addressed in order to

have strong healthy families. It quickly becomes evident that most, if

not all of the other determinants are intimately related to having healthy

families, and that in fact all of the determinants of well-being are interdependent

with all the others. As obvious as this point may seem, many mainstream

health practitioners are still struggling to understand the determinants

of health model. Because of the nature of their scientific and technical

training, it is difficult for many health professionals to escape a linear,

sequential and causal way of looking at health problems, and instead see

an integrated organic system of inter-related factors.

| Basic Physical Needs | Life Sustaining Values, Morals & Ethics | Spirituality & A Sense of Purpose | Safety & Security | Adequate Income & Sustainable Economy |

| Adequate Power | Social Justice & Equity | Cultural Integrity & Identity | Community Solidarity & Social Support | Strong Families & Healthy Child Dev't |

| Healthy Eco-systems & a sustainable Relationship between Human Beings & the Natural World | Critical Learning Opportunities | Meaningful Work & Service to Others | Adequate Human Services & Social Safety Net |

In our own work with such professionals we have found that the medicine wheel is a powerful conceptual tool for helping people to understand holistic and integrative approaches to thinking about health. As we stated in our introduction, the medicine wheel may be thought of as an ancient formulation of the determinants of well-being model. It appears on the surface to be very simple, almost too simple to deal with the complexity of fourteen interactive variables. Actually, it is far more sophisticated then the determinants

imodel, or any of the population health models derived from it.

This is not merely an attempt to say "my model is better than your model". The usefulness of any conceptual model of health development is its ability to show the relationships between the various elements in the process. The determinants model focuses on clusters of determinants, but does not facilitate seeing the whole system within which people are living.

We have found that by using the medicine wheel model in conjunction with the determinants of health analysis, a very useful multi-dimensional picture emerges that can be used to understand not only the interactive relationships between various clusters of health determinants, but also the nature of the overall social system within which the transformation of health conditions must occur.

B. The Medicine Wheel: An Integrative Scheme of Thought to Guide Action

The term "medicine" in tribal tradition refers to any substance, process, teaching, song, story or symbol that helps to restore balance in human beings and their communities. The medicine wheel is an ancient symbol which represents an entire world view (a way of seeing and knowing) and the teachings that go with it.

We have not found a more powerful tool for modeling what is really going on in development processes in any of the sciences and disciplines of the world.

At a midsummer gathering of indigenous nations held at Alkali Lake, British Columbia, Canada in 1986, Phil Lane Sr., a distinguished Yankton Sioux elder, was talking to a large gathering of tribal people representing over thirty-five different tribes and nations.

He held a stick in his hand, and with it he drew a circle in the sand. "Our people used the circle to explain many things," he said. "For instance, the circle represents the hoop of the people. All of the people are a part. No one is excluded. The hurt of one is the hurt of all. The honour of one is the honour of all."

"The human people are not the only people in the circle," the old man went on to explain. "The mineral people, the plant people, those that crawl, those that walk, those that fly, the four leggeds, even the air itself and the water and the stars and planets beyond number--all of these are part of the circle, and so are you, and so am I. What happens to any part of the circle happens to all of us." And thus the elder introduced the concept of deep ecology; of the profound interdependence of all things.

The medicine wheel is simply the circle divided into four parts. Seeing things in fourness, or what Jung called "quaternity," is very common to most indigenous people in the world (we were all once indigenous somewhere).

the whole family,

the whole community, etc.,

The Person

Each human has the potential to develop capacities in four interrelated areas of life:

2. emotional: related to the activities and potentialities of the heart; the feeling self

3. physical: related to the activities and potentialities of the physical body, and

4. spiritual: related to the activities

and potentialities of the spirit self, and having to do (in development

work) with the virtues and values that animate one's life as well as the

capacity to visualize and actualize new potentialities within oneself or

in relationships with others.

At a primary level, most communities consist of children, youth, adults, and elders, as well as other special interest groupings which may also be important to consider because such groups have experiences that are different from the mainstream within the community. Categories of this type might include single mothers, people in recovery, the unemployed, handicapped people, etc.

Using the medicine wheel model of individual potentiality, it is possible to generate a framework for understanding what is really happening in the lives of any particular group within the community. For example, it is possible to consider the conditions and needs of unemployed youth. Their mental, emotional, physical and spiritual well-being can be looked at, both in terms of what it is now, but also what it would be like if it was good (in the ideal sense). Such an examination can best be done by groups of unemployed youth themselves, with the support of those who have allied with them, including a skilled facilitator.

From such a reflection process, a base-line description of current conditions and realities, as well as of the root causes of problems, can be developed. Out of such an analysis will come an understanding of what is needed, and if the momentum from the inquiry process is properly harnessed, one important outcome will be focused action aimed at addressing the challenges faced by unemployed youth. (Appendix A includes a full description of the Community Story Framework, a community analysis, planning and mobilization tool which uses the basic model of the medicine wheel to guide this type of process.)

In each of the four areas (mental, emotional, physical, spiritual), a list of capacities and potentialities can be developed. Some authors call this kind of list a competency profile. The wheel representing the individual person only makes sense, however, if it is seen in relationship to the greater circles of which it is a part.

Appendix B consists of a sample list of potentialities which can be associated with each of the four points of the medicine wheel. They are organized according to the four cardinal directions (compass points). Assigning one of the four cardinal directions to each of the points on the circle is another common way of using the medicine wheel. The device of attaching symbolic meaning related to human capacity to each of the cardinal directions is one that has been used by indigenous people in North America for centuries. In this rendition, a person sees him or herself at the center of the wheel. In order to be a whole balanced person, the gifts and qualities of all four directions must be explored and developed.

The Family or Clan

Healthy families and clans hold their members as a mother holds her children. As children grow in strength and wisdom, only gradually do they learn to be responsible, and to care for those who have cared for them. The family is the womb out of which the community and the nation spring. It is impossible to build a healthy and prosperous community unless and until the families within that community are healthy and strong.

Within the family are four interrelated dimensions of activity and potentiality that are constantly at play:

2. Human Relations - Concerning the nature and quality of the human relationships within the family, and particularly the extent to which those relationships foster human well-being and the unfolding of human potential.

3. Physical Environment and Economy - Having to do with how the family provides for its physical needs, including food, clothing, shelter, safety and security, and the physical health of its members. It is vital to examine to what extent the family's activities in this area of life either contribute to or undermine the overall well-being of the family and its members.

4. Cultural and Spiritual Life - This category includes the beliefs, values, morals and goals of the family. Both what the family members espouse and what they actively practice are important dimensions to be considered. Both affect the overall well-being of the family. This category also focuses on the degree, quality and impact of the family's bonds with the Creator, and the spiritual dimensions of life. It also concerns the degree, quality and impact of the family's bond with the cultural community of which it is a part.

What follows is a model (or map) of the dimensions that are involved in developing a whole community, in its many dimensions and aspects.

Remember that in this study, we are concerned with the challenge of promoting sustainable well-being and prosperity and the unfolding of human potential. As we understand it, individuals have needs and potentiality in the areas of mental, emotional, physical and spiritual development. Individuals don't emerge out of thin air. Nor do they prosper disconnected from other human beings. All of us come from some kind of family, and all of our families had patterns of thinking, of human relations, of beliefs and values, and of physical survival that shaped us.

Families in turn live within communities like fish live in water. The invisible web of relationships that make up community life can either have the aggregate affect of leading to human well-being and prosperity, or to its opposite. Like individual people or families, each community has its own commonality (the personality of the group). In order to effectively initiate strategies that will alter (for the better) the collective habits and relationships that are affecting people's lives within a particular community, it is helpful to be specific about the nature of those relationships and habits.

We map the processes of community health development in four interdependent areas of activity and focus:

2. Social - having to do with the patterns of human relations, and including such related areas as kinship patterns, social protocol, conflict resolution and communication patterns. The social category is especially concerned with the climate of openness and support for individual and group efforts to bring positive changes to their own lives or to the community in general. A useful indicator of health is the degree to which the community is open to and supportive of learning. To what degree is the community characterized by its ability to learn its way into the future?

3. Economic and Environmental - the economic life of the community needs to be understood both in terms of how (and to what extent) people get what they need in order to sustain themselves (in the physical sense of basic needs), as well as in terms of the community's relationships with the natural environment (the eco-system) upon which long-term economic well-being depends. To get a clear picture of the impact of current economic realities, it is important to go beyond income generation to questions related to a) how economic activities are affecting other areas of human well-being; b) how the natural environment is being affected; and c) to the development and maintenance of long-term sustainable systems of production. In many communities, moving from dependency to self-reliance is also a critical component of economic development.

4. Cultural and Spiritual - this category refers to prevailing patterns of beliefs, values, morals and goals that constitute the software hidden beneath the surface of community life. Both what people say they believe in (the espoused or ideal culture) and what they tend to actively do in the pattern of daily life (the lived or real culture) are important. A vital strategy in mobilizing communities is to call people to the values by which they want to live. It is also a fact of life in many communities that there are multiple cultures and value systems that compete and collide within the social space of the community. Usually one or more are dominant, and others struggle for recognition and acceptance. An important indicator of well-being in the spiritual/cultural area is the presence of a vigorous dialogue on values, and a climate of deep mutual respect and appreciation for diversity. The capacity to envision a healthy and sustainable future, and to muster the human will to move together toward creating that future, is perhaps the most important indicator of community well-being that we know.

By the wider world we mean the entire human world outside the community. It can refer to the tribe or nation, the various levels of government up to the nation state and beyond, other countries and regions, or the global monetary market and regulatory systems. Communities do not exist in isolation, free from the impact of the world around them, any more than an individual person does.

In thinking about community health development, it is important to be able to see how any particular community is organically linked to the wider world in which it exists. For example, what happens in the board rooms of major corporations in Europe or America can affect the political and economic well-being of many ordinary people, their families and their communities in Saudi Arabia, Papua New Guinea or Nigeria. A change in the price of oil, (perhaps as a result of a political decision of the Arab Emirate in partnership with other allies) can affect who has a job and who doesn't in Alberta, Newfoundland or Louisiana.

When people lose their jobs, families are affected. Under such stresses, the use of alcohol and drugs and the incidence of family violence tends to increase. And, of course, children are definitely affected. A child who is traumatized by family violence or a marriage break-up can experience intellectual and emotional paralysis. Unable to concentrate or remember or focus, the child fails at school, and begins to act out in ways that cause her to lose friends and to be labeled by teachers and social workers as a problem child. Perhaps a specific label is added to this diagnosis, such as hyperactive and the child may even be given a drug such as Ritalin to control the symptoms.

From this example, taken from actual cases in Canada, it is possible to see what North American indigenous elders meant when they told us "everything is related to everything else." By viewing the world we live within as an interactive system, it is possible to see connections between things that people believe and do in countries and institutions very far away, with what happens in the most intimate relationships (husband and wife, parent and child) in some of the most remote villages of the world (e.g. the Mackenzie Valley in the Northwest Territories or the Niger River Valley in Nigeria). While it is usually not possible to influence or control global political and economic processes, it is possible to create local systems that are not so dependent on the markets or the shifting

sand of political factions.

So, when thinking about community health development in any specific situation, it is vital to understand the wider world in which "the community" exists. Essentially the same four interactive categories which were used to describe the community level can also be applied to the level of the "wider world," but the impact they have on the development process is different enough to warrant further explanation.

2. The Social Environment - referring to patterns of human relations; how the community is affected by such things as racism and prejudice, or a climate of contempt (as is the case, for example, for welfare recipients), and also how the community is able to respond (with open heart or numbed indifference) to the suffering and difficulties of other people. The social climate within which community development takes place can have a very tangible effect (positive or negative) on the community's perception of its own capabilities. Managing public opinion and winning outside support for development efforts is vital and necessary for many reasons, some of them political and economic, others related to internal dynamics such as a belief in your own dreams or the legitimization of community leadership.

3. The Economic and Ecological Environment - refers to the economic and environmental realities within which the community's development takes place. Economic and environmental conditions at the local, regional, national and even international level can influence the outcomes of community efforts. It is therefore extremely important that as communities act locally, they are thinking globally.

4. The Cultural Environment - this category refers to several dimensions. First, it refers to the tension between the dominant culture and the culture of the developing community. Alvin Toffler called the dominant culture "indust-reality" (Toffler), or the reality system of the industrialized countries and regions of the world, characterized by the software of such values as individualism, materialism, scientism, centralization, synchronization, massification, etc. A spin-off of the global dominant culture is that the organizational and bureaucratic cultures of Euro-American businesses, military and government organizations have all merged in a kind of global super-culture of the workplace. Nearly every government office, United Nations Agency and humanitarian organization in the world operates following the hidden rules of that dominant culture. An assumption of the dominant culture is that all other cultures are inferior, or primitive, or at least limited to the private (i.e. non-business, non-professional) sphere. The dominant culture drives almost all professional agencies’ actions anywhere in the world in the fields of health, education (such as schools, colleges and universities) and social welfare.

The critical reality relative to community health development in Aboriginal communities is this. The culture of the community may well conflict with the dominant culture driving the agencies that serve it. Almost all helping agencies (which unconsciously follow the rules and accept the basic assumptions of the dominant culture) work at cross-purposes with communities that are marginalized by, or are ethnically outside the dominant culture.

Indeed, the dominant culture tends to be blind to the very existence of cultural diversity. Its perspective, when viewing peoples who are "different", is that they have culture-- those strange people with their quaint ideas, their customs, languages, costumes, music, diet etc. -- they have culture, and we have reality. We know we have reality because the scientific method proves that our world is the real world. Such complete cultural arrogance is blinded to other people's way of knowing, and is unable to value other people's knowledge and experiences. The result is that many community insights are discounted or simply not heard and heeded.

The tragedy of all of this is that Aboriginal communities often internalize the perceptions the dominant culture has of them. They begin to doubt what they know and to reject what they have experienced as being somehow inferior or unimportant. Yet people can only develop based on who they are (not on who they are not) and upon what they have and what they know (not on what they don't have or what they lack). The self-doubt created within communities about their own value and worth and their own capacities is a very serious obstacle to authentic human and community development.

Helping communities to sort out their own cultural foundations from the dominant culture, and to learn to "be themselves" in a multi-cultural world is vital to success in sustainable development processes. A profound implication of this sorting-out process must occur at the level of belief, values, morals and goals. The spiritual life of most communities in the world has been undermined by the dominant culture media, and the undertow of individualistic and materialistic values.

Survival into the twenty-first century may well depend on the re-birthing of true community. The core of that process is binding the hearts and minds of the people to life-sustaining, life-enhancing values and beliefs. Unless love, forgiveness, honesty, and unity in diversity characterize our communities, they can not survive; and if they do not survive, it is unlikely that many of us will either.

Fitting it all Together

When we talk about human and community development, we are talking about all of the following:

2. The development of the family (or clan) and small groups with respect to dominant thinking patterns, human relations, physical environment and economy, and cultural and spiritual life.

3. The development of the community with respect to its political and administrative, economic, social, and cultural and spiritual life.

4. The context of the wider world within which human and community development is taking place. This context includes the political and bureaucratic environment, the social environment, the economic environment, and the dominant cultural environment.

No matter at what level you try to intervene, you are actually always dealing with all the levels.

For example, an economic development officer in the eastern Canadian province of Newfoundland may be trying to work on job creation. She is struggling against the reality that the economic climate of the region in which the community is located is depressed because of the collapse of the cod fishing industry, due to over fishing. This problem is made worse by the fact that governments are short of money and can't afford to keep the entire population on welfare or subsidized make-work programs. These are all global conditions (i.e. the wider world in the model) affecting local development efforts in Newfoundland. Considering the ecology and economy of the region, the economic development officer tries to encourage people to start small businesses. But many families have either been fishermen or fish-industry-dependent for generations. There is a prevailing belief (mostly unconscious) in many families that if you can't go fishing (or some other sea harvest activity) there is really no option except welfare or unemployment insurance. Additionally, the hard times caused many men to turn to alcohol for comfort. With alcohol comes a legion of social problems affecting families and children.

Clearly, in this case of Newfoundland traditional fishing communities, the challenge of reviving the economy can only be addressed by taking into consideration all four interacting levels in the model (individual, families, whole communities, and global conditions). Indeed, after the initial shock (1994), what has now begun to happen in Newfoundland is that communities have started coming together to talk, to support each other, and to build solutions. Many creative alternatives are still emerging. But almost everywhere, when positive development has begun, it has emerged out of a community re-creation process, and not out of the implementation of a technical solution.

In this section we have outlined the dimensions of need and potential growth within individuals, families and groups, communities and society at large (i.e. the world). Basically, we are presenting a tool for thinking about how the various dimensions and levels fit together and interact. Each level of development (presented in the model) takes place within a broader level.

Individuals develop within families, groups and organizations. Families develop within communities, and so do groups and organizations. Communities and organizations develop within the context of surrounding societal and global conditions. The diagram below illustrates how all the dimensions and levels mutually influence each other.

The Wheel Turns

The models and concepts presented so far have identified the areas of need and potentiality in human and community development. What it has not shown is anything of the process of change. What follows introduces the key elements that drive growth or development. The wheel, made of interlocking wheels within wheels (see diagram above) turns through processes of learning and transformation. These processes are propelled by certain key dynamics of change.

2. Imagination - It is impossible to enter into a condition that we cannot imagine. Being able to see ourselves becoming healthy or prosperous or unified is a necessary prerequisite to creating the conditions within ourselves and in our lives that will create those described future conditions.

3. Learning - In human and community development, learning is the process of acquiring the attitudes, beliefs, knowledge and skills to make the changes that are needed within ourselves or in our families, organizations and communities. It is never enough to have a vision and to make a plan. Most of us have habitual ways of thinking and acting. These old habits of thought and action have created the world as we know it. No matter what we visualize or desire in our future, if we keep thinking and acting in the same old ways, we will always get the same old results. If we are to create a new kind of future for ourselves (or within our families, organizations or community), we will need to learn new ways of thinking and acting that will lead to the new outcomes we desire.

4. Volition/Participation - The word volition means will power. In personal development "volition" refers to the exercise of focus or attention, choice and perseverance in moving toward goals and in carrying out plans. When we talk about the exercise of will within communities or groups of people we use the term participation. Participation in community health development means the meaningful involvement of the people whose lives are being affected by the process of development in all parts of that process (analyzing issues or problems, discovering solutions, making plans, implementing strategies and projects, and evaluating outcomes).

Part I of the report has been exploring a conceptual framework for human well-being and prosperity, the true foundation for a viable social security system for Aboriginal communities. The first section put forward a working list of the determinants of health, synthesized from consultative processes with many Aboriginal communities. A second section used the medicine wheel as a way of expanding the determinants of health approach into an integrated model which can be used as a basis for integrated community healing and development planning. This next section explores principles which can be used to guide the development of a social security system for Aboriginal community.

What’s a Principle?

A principle, as we are using the term is a statement of basic truth about some aspect of the process of human and community transformation. It articulates what works or what doesn’t, what is needed, what must be avoided, how the process must proceed, and what it must include if the outcome is to be authentic human well-being and prosperity, and not some counterfeit. And there are many counterfeits. Much is said and done in the name of "health progress", "development", "improvement" and "prosperity" that either ends up benefiting a few at the expense of many others, benefitting no one, or else bringing real harm to people or to the earth.

The following presentation of sixteen principles is the outcome of consultations and experiences with Aboriginal elders and communities from all across North America, as well as systemmatic reflection based on many field applications. There are, of course, many ways these principles could be expressed, and so these are offered as a work in progress, which needs to be adapted by each community for their own particular needs and way of expressing themselves.

1. Human Beings Can Transform Their World

The conditions of our lives are not unchangeable givens. We are not trapped in the world as we know it. How things are now is not how they always were nor how they will always be in the future. Indeed, the most fundamental characteristic of the universe is change. Although many of us live within the illusion of permanence, the reality is that our lives and the world around us are in a constant state of change.

Many challenges and difficulties we face as human beings everywhere on the planet are either the result of our own actions or those of other people. To a large degree, human beings make the human experience what it is. We continuously violate each other and the natural world upon which all life on earth depends. As a human family, we dwell within the web of relationships we have made with other people, nature, and the spiritual world.

The totality of the impact that web of relationships has on our lives, on future generations and on the earth itself is what can be referred to as the human predicament. Prosperity and poverty, sickness and wellness, justice and oppression, war and peace -- all of these are products of those fundamental relationships.

It is of the utmost value to know that those relationships can be changed. It may be very difficult, it may take great vision, sacrifice and effort, and it may require time to unfold, but the people need to know that healing and development are possible.

In practice, the application of this principle implies making a shift from being a passive recipient, or victim, of the realities and conditions within which we find ourselves living; in other words, "stepping into history" (Freire, 1970). Moving from the passive to the active state begins in consciousness. It begins in how we see ourselves within the process of life as it unfolds.

This active approach of entering into a creative relationship with life, and of consciously making choices that will lead to the making of a better world is the choice of "stepping into history." Gandhi and his followers did it in India. Thousands did it in the former Soviet Union. Nelson Mandela and the ANC did it in South Africa. Phyllis and Andy Chelsea did it in Alkali Lake, British Columbia. And when they did it (each of them), they changed the course of history.

2. Development Comes from Within

The process of human and community development unfolds from within each person, relationship, family, organization, community or nation. Outsiders can often provide catalytic support in the form of inspiration, technical backstopping, training or simple love and caring. But because the essence of what development is entails learning and the transformation of consciousness, there is no way to escape the need for an inner-directed flow of energy.

For example, a child learning to ride a bicycle may need a certain amount of encouragement, and may even require a bigger person running alongside her to support the bike while she learns how to balance. Still, there is no getting around the need for the child herself to get up on the bike and to try to ride it. No amount of explaining, or riding the bike back and forth in front of the child to demonstrate how to ride, will replace doing it.

In a similar way, people who are struggling to learn new patterns of life and to transform their world need to drive change processes themselves if those processes are to be effective and sustainable. Development comes from within.

3. Healing is a Necessary Part of Development

Healing the past, closing up old wounds, and learning healthy habits of thought and action to replace dysfunctional thinking and disruptive patterns of human relations is a necessary part of the process of sustainable development.

Many wonderful projects and programs have been destroyed because the people

involved in them were unable to trust each other, to work together, to communicate without alienating one another, or to refrain from undermining each other, tearing each other down and attacking each other.

In some communities, alcohol destroys human potential and causes people to retreat within the bottle to deal with problems that need to be addressed in cooperation with others. In other communities, generations of in-fighting and mutual hostility across family, cultural, clans, religious or political lines block any chances of unified action. In still other organizations and communities, certain personalities or groups hold the reins of power, and thereby control the conversation of the community to such an extent that other people simply fall silent and retreat.

Many individuals, because of their family background and personal history, carry a great deal of resentment or fear or numbness that serves to paralyze them in terms of building effective relationships with other people. These old hurts, and the habitual responses to hurt that people carry, may well be there for good reason. Some people (and sometimes whole populations) have experienced horrendous suffering, and are carrying the burden of unresolved pain and conflict inside them. It is therefore critical for people to learn that these habits of the heart and the dysfunctional behaviours that go with them can be overcome and left behind. The processes for doing just that are what we mean when we say "healing". As long as these habits remain in place, people will be handicapped, and even paralyzed and blocked from full participation in development processes.

4. No Vision, No Development

A vision of who we can become and what a sustainable world would be like works as a powerful magnet, drawing us to our potential. Where there is no vision, there is no development.

If people cannot imagine a condition other than the one they live within now, then they are trapped. It is only when we are able to see ourselves in terms of our potential and within healthier and more sustainable conditions that we can begin to move towards creating those conditions within ourselves and in our relationships with the world around us.

Helping people to develop a vision of a healthier and more sustainable future that they can believe in and identify with is therefore one of the primary building blocks of success in development work.

More deeply, culture is the soil in which the tree of identity has its roots. People's sense of who they are, and of their self-efficacy is bound up in their (often unconscious) connections to their cultures. To disconnect or alienate people from their cultural foundations is like plucking a plant from the soil in which it is rooted.

The eminent American futurist, Willis Harman, had this to say about culture:

Not only do distinct cultures have unique perceptions not experienced by other cultures, but they also have unique gifts and abilities. They can know things, see things, experience things, and do things that people from other cultures cannot. This is a very important discovery. It means that each distinct cultural group has people with unique strengths and capacities upon which healing and development can be based. You cannot build on what is wrong or missing. You have to build on who people actually are and what they have. It also means that the effective approaches for solving actual social and economic problems may look very different in different cultural communities.

Following is a list of some key areas related to healing and development that need to be guided from within the culture of the people. We spell out those points in some detail in order to stress that almost all cultures have ways of doing all of these things. It is very

important to help people to discover their own ways of addressing each of these areas.

b. The analysis of current realities, conditions, and needs.

c. The interpretation of how the past has shaped the present and how outside influences have affected everyday life.

d. A description of a sustainable future that is desirable and possible (i.e. a vision).

e. An articulation of the values and principles that will guide development action.

f. The selection and priority setting of the goals of development.

g. The selection of healing and program strategies.

h. The making of the plans.

i. How the health development promoting organization is structured and how the program functions, who controls it, how it runs on a day-to-day basis, who is selected to work in it (and how this selection is made), how the organization fosters the participation of the people it serves, how conflicts are dealt with, how accountability is handled, and how money is managed.

j. The indicators of success that are chosen.

k. Evaluation of the process and the outcomes.

l. How healing and development experiences are interpreted and ploughed back into new analysis and new efforts.

6. Interconnectedness: The Holistic Approach

Everything is connected to everything else. Therefore, every aspect of our healing and development is related to all the others (personal, social, cultural, political, economic, etc.). When we work on any one part, the whole circle is affected.

The primary implication of the principle of interconnectedness for development practice is the requirement of taking a whole systems approach. This means that we can only really understand a particular development challenge in terms of the relationships between that issue and the rest of the life-world in which that issue is rooted.

For example, in many tribal communities, alcohol and drug abuse can not be understood by focusing on the medical fact of chemical dependency. It is only when we consider the historical and cultural context in which the abuse is taking place that it becomes clear how substance abuse (in those communities) is a social phenomenon with profound spiritual roots. Once this was recognized, many North American tribal communities began to address the issue of alcoholism by combining personal healing, counselling, economic development and cultural revitalization. All of these dimensions needed to be addressed on a community-wide basis before individuals in significant numbers began to leave alcohol behind. Many communities that have taken this holistic approach have gone a long ways toward eliminating alcohol from the community system.

The principle of interconnectedness provides the following critical guidelines for community work. Personal growth and healing, the strengthening of families, and community development must all go hand-in-hand. Working at any one of these levels without attending to the others is not enough. Personal and social development, as well as top-down and bottom-up approaches must be balanced. This is the true meaning of a holistic approach in community development.

The point is this: we all must live in a common social environment. We have recently begun to learn that if we poison the air we breathe and the water we drink (i.e. the environmental commons), we are poisoning ourselves. Similarly, if we poison our relationships with other people who live in the same social world as we do (the social commons), then we and our children will sooner or later discover that we have poisoned our own lives.

The primary implications for community healing and development of the principle, "the hurt of one is the hurt of all; the honour of one is the honour of all," are fairly straight-

forward:

b. It is vital to foster a spirit of mutual respect and cooperation, such that improvements and accomplishments in the lives of some people are seen to be an achievement for the whole community.

c. Similarly, it is essential that the community believes (and acts upon the belief) that the misfortune of anyone is the business of everyone.

What we think about expands in our lives. If we espouse separateness, we create it. For this reason, increasing the community's capacity to see itself as inter-connected -- as one -- is a very powerful strategy for generating sustained cooperative action. Because we live in a world of competing dreams and ideologies, it is vital to nurture and deepen the community's ability to be animated by the vision of our common oneness and our mutual responsibility to serve and protect one another.

8. Unity

Unity means oneness. Without unity the common oneness that makes (seemingly) separate human beings into community is impossible. Without a doubt, disunity is the primary disease of community.

Science tells us that the physical universe is made up of billions upon billions of tiny particles called atoms, bound together in fields of energy. These energy fields take many different shapes and patterns: stars and planets, trees and rocks, fish and fowl, and human beings. Clearly there is some cohesive force that holds the particles together in the forms that we see in our world. Imagine what would happen if the cohesive force that holds all of the particles together that make up the Rocky Mountains were to disappear. The mountains would simply crumble into dust. In the human world, the cohesive force that binds us all together is love. While most spiritual traditions on the planet have been trying to tell us this for centuries, science is only now beginning to come to grips with it. We have now learned, for example, that people who feel the love, support and caring of family, friends and community have stronger immune systems, and are therefore more resistant to disease than people who feel isolated, alone and cut off.

When human beings are connected to each other in a complex web of relationships for mutual support and cooperation, it doesn't matter what area of life these relationships focus on (governance, economics, recreation, the arts, etc.). If the feelings between the people are good, then the enterprise will probably flourish. Conversely, if the feelings go bad, the enterprise will probably fall apart, no matter how clever the plans and strategies of the group may be.

What is critical to realize is that building and monitoring common oneness (i.e. community) requires the involvement of the human heart and spirit, as well as our minds (thinking) and our physical energies (i.e. time and work).

Unity is the term we use for the cohesive force that holds communities of people together. It is a fact of our nature as human beings that we need the love, support, caring and respect of others in our struggle to heal ourselves and develop our communities. Unity is the starting place for development, and as development unfolds, unity deepens. The strategic implications of this vital principle for Aboriginal community healing and development is that restoring and maintaining unity must be seen as a pre-requisite at the foundation of the community healing process.

9. Participation

Participation is the active engagement of the minds, hearts and energy of people in the process of their own healing and development. Because of the nature of what development really is, unless there is meaningful and effective participation, there is no development.

On the personal level, we use the term volition (the exercise of human will) to refer to the capacity to focus, to choose, to adopt goals, to persevere and to complete what we set out to do. We refer to this capacity as will power. Nothing can be achieved in our life (and all of our hidden potential remains dormant) unless and until we engage our own volition. As human beings, we must direct our energies toward a goal in order to achieve it.

This is also true of communities, and the collective will of the community is engaged through the process of participation. Since authentic development is driven from within, through learning (i.e. acquiring capacity) for personal and social transformation, there is no escaping the necessity of involving the people whose development is being promoted in every aspect of the process.

Participation is to development as movement is to dance or the making of sound is to music. If you take away sound, you have no music. If you take away participation, you have no development.

The term participation is used to refer to many different types of involvement on the part of community members. Not all of these are equally valid in view of the definition of authentic development explored above. Appendix C presents a chart describing these various types of participation in terms of their relevance for community healing and development work, as well as some common barriers and obstacles to participation.

This type of "development" is one of the primary causes for the alienation of hundreds of millions of youth around the world from their communities and cultures. It is often the principal cause of the breakdown of law and order and the true source of many ethnic conflicts, some of them prolonged and deadly.

Unless justice animates all that we do in human and community work, what we are doing is not development.

In down-to-earth terms, this understanding implies the following:

b. Drawing on the wisdom, teachings, principles, laws and guidance that come from the rich spiritual traditions of the people to inform our understanding of the goals, purposes and methods of development.

c. Practicing life-preserving, life-enhancing values, morality and ethics (such as honesty, kindness, and forgiveness).

d. Strengthening our spiritually based development capacities, which include:

ii. the capacity to believe in that vision, dream or goal to such an extent that one is able to align one's heart and mind to its achievement;

iii. The capacity to express that vision, dream or goal through language, mathematics or the arts;

iv. the capacity to actualize that vision, dream or goal through the exercise of our volition (i.e. our will) to choose, plan, initiate, persevere through difficulties and complete processes of growth and development.

12. Morals and Ethics

Sustainable human and community development requires a moral foundation. When morals decline and basic ethical principles are violated, development stops. Essentially, moral and ethical standards describe how human beings must think and act toward themselves, the Creator, each other, and the earth. There has never been a successful society in the history of the planet that did not have moral standards, laws and protocol that people were required to follow.

Moral and ethical standards are not mere limitations imposed on our freedom by the conservative or the prudish. On the contrary, these standards describe where the boundaries of well-being may be found. They are like highway signs that tell us to slow down on this corner, to be careful on that hill, or to drive with caution when the road is slippery. We can choose to ignore them, but we do so at our own peril.

In healing and development work, the violation of moral and ethical standards can destroy months and even years of good work. Like a young plant just breaking ground and experiencing the heat of the sun and the strength of the wind and weather for the first time, developing people are often very vulnerable. It doesn't take much to destroy their faith and confidence in themselves, or in the processes of growth. In those early stages, people often look to their facilitative leaders and professional helpers to be role models of wellness. In a sense, these facilitators are living proof that the process is real, and that the dreams people have dared to believe in can come true. Later, when they become stronger and more self-reliant, they will learn to see the strength they are looking for within themselves. But even then, the violation of ethical and moral standards can seriously undermine personal growth, healing, and community development processes. The most common violations that cause trouble all over the world are the following:

b. Sexual Misconduct - sexual relations between professionals and clients, or trainers and community learners or sexual abuse of children or the weak and vulnerable (ranging from seduction to rape, but always containing the element of the more powerful taking advantage of the weak and vulnerable).

c. Alcohol and Drug Abuse - ranging from closet addictions to open drunkenness. This problem usually causes many others, such as accidents, a breakdown of morality, and a general collapse of discipline, responsibility, accountability and the quality of work.

d. Backbiting, Slander, and Gossip - speaking negatively about others, or spreading "information" calculated to undermine the reputation and the public trust and confidence of others is one of the most destructive behaviours impacting the heart and soul of community wellness. This is because such behaviour destroys unity. It sets up barriers between the hearts and minds of people. It corrodes trust and rots away common oneness. Nothing dampens the enthusiasm of the people for participation in community healing development activities more effectively than poisonous talk. Usually, at the root of such talk may be found hurt, jealousy, or competition for power, influence, or money.

Learning is the process of acquiring new information, knowledge, wisdom, skills or capacities that enable us to meet new challenges and to further develop our potential. Learning leads to relatively enduring changes in behaviour. Individuals, families, organizations, communities, and even whole nations of people need to learn.

Because learning is the key dynamic at the heart of human development (in one sense, since we can say that human development is a process of learning), there is no way of separating learning from the process of community health development either. Unless people are learning, community health development is not happening. This principle tells us that the promotion of various kinds of learning is an important part of what individuals and agencies who are facilitating community healing and development initiatives must be doing.

For purposes of devising learning strategies in healing and development work, we have found that distinguishing the following categories (or types) of learning has been helpful.

b. Transformational Learning - enabling people to see possibilities and potentials within themselves, and to envision a sustainable, desirable and attainable future. Transformational learning is also learning to generate and sustain the processes of healing and development that constitute the journey to a sustainable life.

c. Relational Learning - refers to learning for inter-personal well-being. Relational learning involves the acquisition of virtues and the practice of values that promote good human relations. It also involves learning the skills and positive interaction patterns that lead to healthy human relations. Relational learning requires learning together with other people because much of what needs to be learned is connected to the habits of thinking and acting that only arise when people are together.

d. Operational Learning - refers to everything we need to learn in order to accomplish what we need to do in the process of healing and development. Operational learning includes acquiring:

ii. in-depth knowledge and wisdom,

iii. new skills,

iv. new behaviours and habits, and

v. new values and attitudes.

14. Sustainability

b. Environmental (or bio-system) sustainability - refers to the well-being of the natural systems upon which all life on earth depends. The quality of air, water and soils, the preservation of fish and wildlife habitat, and of forests, inland waterways, reefs and oceans, bio-diversity and the integrity of the gene pools at the base of life are all issues related to the sustainability of the natural environment. The global environmental crisis is the result of many people in many places taking actions that may have brought wealth to some groups, but has also caused serious damage to the natural environment upon which other people and future generations depend for their survival and well-being.

c. Social and cultural sustainability - refers to how development action impacts the social world of the people. There are many kinds of development that bring one kind of improvement along with another kind of harm to communities. Community health, cohesiveness, self-reliance and culture are a few of the dimensions of life that can be affected. For example, along with the Alaska pipeline and North Slope development came an increase in alcohol and drug abuse and family violence, and a disconnection from the land and their own culture for many Alaskan Native people. All over the world, dominant culture schooling educates the children of minority cultures into devaluing their own identity and mistrusting their own cultural resources. Very often when money comes into a community for a development project, people are pitted against each other for control of the process and for a share of the benefits. In each of these examples, one kind of benefit brought another kind of deficit.

d. Economic sustainability - refers to the continuous production of wealth and prosperity. If a community depends on fishing (as many in Newfoundland did) and has no other means of earning a livelihood, the ability of that community to sustain itself over the long run is utterly dependent on the continued abundance of fish stock, as well as on market conditions for the sale of fish. Clearly, economic sustainability (like biological sustainability) is enhanced by a diversity of strategies. Economic sustainability refers not only to producing wealth, but also to the equitable distribution of that wealth so that all members of the community can meet their basic needs.

e. Political sustainability - refers to the processes through which decisions are made and power is arranged and distributed. A community development process is not sustainable if the political forces against it are stronger than the political forces within it. For this reason, it is very important to win over the support of political leaders and organizations that control the political and economic environment in which community development is occurring.

Likewise, in community health development work, it is much more fruitful to focus energy on building the alternative than it is to try to oppose and undermine what we do not like. This in no way implies that we should allow injustice or unhealthy conditions to continue. The principle of moving to the positive suggests that we should clearly visualize what it is we wish to achieve in terms of positive conditions (health, prosperity, social justice, racial unity) and begin building that. Instead, many people focus their program energies on trying to eliminate the perceived obstacles to the things they wish to achieve.

Consider the example of disunity in a community. One approach to solving this problem might be to identify the people we believe are the source of the problem and to attempt to convince them to change. Unfortunately, when confronted with a challenge to one's character or personal behaviour, many people become defensive. A usual response includes one or all of the following: a) deny that there is a problem, b) discredit the person who challenges you, c) blame someone else for the problem, or d) justify the behaviour for which one is being criticized and increase it.

Another approach to disunity would be to gather together those people who want unity and to begin to behave toward each other in a unified way. The result of this strategy is that you have created unity. Other people can join this new pattern, but if they wish to partake of its benefits, they will need to behave according to the principles and rules that produce unity.

While this may be a somewhat simplified example, it is in fact a very powerful community healing and development strategy. Many North American tribal communities have already created sobriety movements that will eventually end the terrible burden of community alcoholism using this strategy. Recovering alcoholics and non-drinkers formed core groups and worked on their own healing as well as the creation of healthy human relations between them. Gradually these islands of health attracted others, and the core groups grew in strength and influence until a critical mass was reached and whole communities were transformed.

In whole health development processes, the most powerful strategies for change always involve positive role modeling and the creation of living examples of the solutions we are proposing. That is why, as development practitioners, we must strive to be living examples of the changes we wish to see in the world.

This principle also applies to development-promoting organizations. A sick organization cannot promote health. An organization crippled with in-fighting and disunity cannot build community in the world. Unless our organizations reflect the principles and values we espouse in our work with the people, why should anyone take us seriously? By walking the path, we make the path visible.

D. The Big Picture

There is no escaping the fact that Canadian Aboriginal people are a part of the human family. And while it may be easier not to think about it, there can be no doubt that whatever is happening to the rest of the world is also happening to Canadian Indigenous people.

Much has been written in the past several decades about large global patterns and trends that are sweeping across all boundaries and affecting everyone on the planet, regardless of geography, culture or national identity.

Following is an abbreviated summary of global patterns and trends that we believe are of particular significance to the process of promoting well-being and prosperity in Canadian Aboriginal communities. In addition to listing the trends, we have selected two of them for further discussion because we feel these two will have an extraordinary impact on community healing and the process of social security reform.

brings health, economy and environment into an integrated strategy.

2. Global Corporation versus Local Economy - There is a very powerful pattern of large corporations working as a group (i.e. a network) across many national boundaries to ensure the steady growth of their businesses and profit. A part of this pattern is to put constant and sometimes painful pressure on governments everywhere to remove barriers that might interfere with "growth"--"barriers" such as social concerns, the protection of local economies, and environmental protection regulations. An aspect of this pattern is to convince governments to shift spending away from social programs (health, education, social security, etc.) and instead to subsidize corporate initiatives. This is often done in the veneer of "job creation." In many countries, the economic "crises" people are experiencing (which has led to extreme hardships and suffering in many places) is created by these forces. The gap between the wealthiest and the poorest is widening everywhere, and the sheer numbers of the poor are increasing.

3. Population - The world's population is increasing by nearly one hundred million people a year. In many places this is undermining hard-won gains made in health, food production and other aspects of human betterment. Development is not able to keep up with the sheer numbers of people that need food, shelter, medical care and a means to earn their livelihood. Increased population pressure is also forcing the poorest everywhere to further undermine the natural environments they live in, as people cut down forests for fuel and space to grow food or otherwise overuse or abuse the environment in a desperate bid to survive. The essential problem is that more people need more resources. And there is always a limit to how thinly resources can be spread.

4. Social and Cultural Disintegration - The basic social and cultural relationships of human beings and their communities are rapidly disintegrating. The signs are present everywhere. For example, there is a global youth crisis. Large numbers of young people in every country on earth feel angry and disconnected from their families, their communities, and from any hope for themselves in a healthy and prosperous future. Violent crime, addictions, communal and family violence, sexual abuse, divorce and family disintegration, and the breakdown of trust, mutual cooperation and a sense of common oneness (the real meaning of community) and purpose are all clear signs of this deadly pattern of disintegration. Nor is any people exempt. The squatter settlements of the poor in Africa, Latin America and Asia, as well as the urban "jungles" of America are equally stricken. Even the children of the rich have been affected. It is important for Canadian Aboriginal communities to know that much of what they are experiencing in terms of human crisis is also occurring worldwide.

5. People's Empowerment versus Political and Economic Repression - On the one hand there is an unmistakable demand for a voice and power coming from the masses of community people in every country. It is clear that people everywhere are determined to gain some measure of control over the forces and conditions most affecting their lives, and that they are no longer willing to remain passive victims of political, economical and social forces.